|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

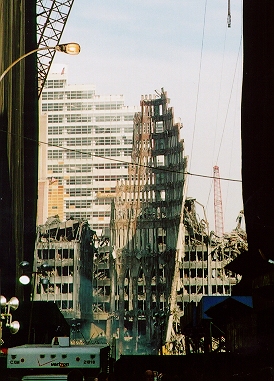

"Downtown Manhattan, that canyon land of skyscrapers and financial houses, has suffered economic blows that exceed the grim forecasts made after the attacks on the World Trade Center. The New York Stock Exchange has backed away from a proposed $1 billion, taxpayer-subsidized new home because its stockbrokers fear occupying a gleaming office tower. About 8,000 tenants have not returned to the upscale apartment buildings that skirt the western edge of the World Trade Center site. New Jersey officials, after promising not to profit from the city's misery, are dangling $35 million in cash incentives to lure financial firms from Lower Manhattan. Downtown businesses have already moved 19,000 jobs to New Jersey; in all, Lower Manhattan has lost 100,000 jobs. In mid-September, New Yorkers talked of rebuilding as a patriotic duty. City officials offered to streamline regulations and developers promised to renovate and build new offices for displaced financial and legal firms. Some economists even spoke of a post-disaster boomlet, as federal aid and insurance money poured into the city.

Reality has proven gloomier. The economy has spiraled downward, hundreds of small businesses have shuttered rather than move to other downtown sites and many large financial firms view an exclusive base in Lower Manhattan as too risky.

Far from the shortage of space that was predicted right after the World Trade Center attack, downtown New York has 13 million square feet of vacant office space, twice as much as two months ago. 'The blow to Lower Manhattan is massive,' said Kathy Wylde, president of the New York City Partnership, which represents the companies that comprise the city's business elite. 'This is not a question of office space; the shock to Lower Manhattan is much greater than anyone realized.'

The Partnership and the Chamber of Commerce co-authored a report last week that found a gaping hole in the city economy, particularly near the World Trade Center site. 'The damage is concentrated in Lower Manhattan,' the report stated, 'which lost 100,000 jobs and almost 30 percent of its office space. This puts at risk many of the 270,000 jobs still located south of Chambers Street.' The collapse of the towers badly damaged a once-fertile economic ecology. Measured by gross sales, the World Trade Center retail stores alone -- which occupied a half dozen floors of the 110-story towers -- comprised the fifth-largest mall in the United States. The now-destroyed Borders Books on its ground floor was the highest grossing store in the company's chain.

The downtown financial services industry lost $4.2 billion. And smaller businesses on the streets around the towers, from Brooks Brothers to Big Lady discount emporiums, from cheeseburger diners to three-star restaurants, lost tens of millions of dollars. Some businesses closed, and many more soldier on in a twilight of permanent half-off sales. The boutique architecture, high-tech and graphic art firms that helped revive downtown after the recession of the early 1990s have seen precipitous declines in business. Several of their largest remaining clients, from American Express to Lehman Brothers, are moving uptown, at least temporarily.

'We're realizing how many small firms down here fed directly off the financial industry,' said Jonathan Bowles of Center for an Urban Future, an economic and social development think tank on Wall Street. 'These firms have lost their anchor.' Downtown's physical disrepair presents another knot of problems that could take years to untangle. Transportation remains a mess. Forty percent of downtown workers live in New Jersey, and most commuted on the PATH commuter train each day. The sole PATH station in Lower Manhattan lies buried under thousands of tons of debris, and the average commuting time has doubled. Electric service has been temporarily hot-wired, as utility workers compensate for two destroyed substations by running large black bundles of electrical cords across streets and sidewalks. Telephone service is spotty throughout downtown, and a walk of just a few blocks can take 20 to 30 minutes as one negotiates construction sites and police checkpoints. And there are the smoldering underground fires at the site that burn and burn, and emit a terrible smell.

In the days after the attack, downtown landlords made lavish promises of quick renovations. Brookfield Properties said tenants would return within two weeks to sections of the World Financial Center, which sits directly to the west of the World Trade Center and was badly smashed. Ten weeks later, the buildings remain vacant. James F. Gill, Battery Park City Authority chairman, expressed the hope that tenants would flock back to the residential towers. About 12,000 have returned -- but 8,000 have not.

Now, he mixes a defiant optimism -- 'We'll lose some tenants, and others will take their place in our beautiful and beloved city' -- with a dour realism. 'When the wind blows the wrong way, it's not pleasant,' Gill said. 'There are bodies under that wreckage.' Lower Manhattan has acquired the curious status of tourist war zone. The pilgrimage to the site has become a celebrity rite of passage for everyone from Vice President Cheney to the president of Mongolia.

This no doubt builds a well of national sympathy for New York. But few Fortune 500 businesses see a competitive advantage in being located near anything known as ground zero. 'Lower Manhattan has the core problem of being very unpleasant now,' said Mitchell Moss, director of New York University's Taub Urban Research Center. 'The networks have as their visual image cranes digging for bodies. The great risk is that a lot of firms look at that and leave.'

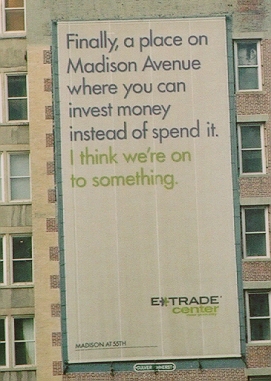

In fact, that's already happening. Some investment banks and law firms have taken 30,000 or so jobs and migrated toward midtown, which is the city's most lucrative business district. Other corporations wander farther away. After Sept. 11, New Jersey officials promised not to pick at New York's wounds and steal away its downtown businesses. Those promises had a short half-life. In the last few weeks, New Jersey has offered $35 million to lure six large financial firms across the river, and at least one firm is expected to bite. (Electronic signs on the New Jersey Turnpike helpfully advise motorists to avoid southern Manhattan). 'I find it very distasteful,' said Michael G. Carey, president of the city's Economic Development Corporation. 'They're offering extreme high-end packages to try and take our corporations. How about some compassion for a sister city?' None of which is to suggest that Lower Manhattan is finished. The Federal Reserve, the New York Stock Exchange -- which for now will remain in its quarters on Broad Street -- and Deutsche Bank are among the institutions that add weight to the nation's oldest and mightiest financial district. And some see the catastrophic as hastening the inevitable: the slow metamorphosis of downtown into a place that mixes the residential and the cultural with the financial.

Mitchell Moss of New York University argues for flipping the role of Lower Manhattan, taking advantage of its breathtaking harbor views and parks and turning it into a cultural, residential and business destination. Wylde of the New York City Partnership doesn't disagree, or not entirely. She notes that many business and political leaders, not least Mayor-elect Michael Bloomberg, have spoken of rethinking downtown development. 'There is a concern about having too many [high-end financial] people concentrated in one place,' she said. 'But in the rush to diversify our economy, we can't lose sight of the fact that we had one of the world's great economies down there, and that's important to the whole United States.'" (Michael Powell, The Washington Post, November 26, 2001)

|