|

|

|

|||||||

|

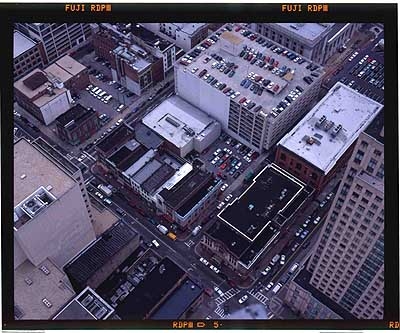

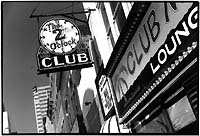

" "Our values have changed," Joanne Attman proclaims. Attman and her husband, Ely Attman, own the building at 425 E. Baltimore St., and are thus the landlords of Club Harem, a strip club in Baltimore's red-light district, the Block. "There's nothing wrong with sex," she says in a telephone interview. "There just isn't. It's an adult thing, and as long as it stays an adult thing, that's all that's important. "You know," she continues, "we've come a long way, and people do not view sex as a bad thing if they can do all that's on the Internet, do what they do on TV, and on the phone. So, as far as the Block, the Block is benign." The Attmans, like most of the owners of Block property and businesses, do not live in Baltimore City. Their abode, most recently assessed at more than $225,000, is in a new development in Pikesville. Being a nice, suburban couple, the Attmans probably don't often come down to the Block and look around; as Joanne Attman says, "We don't really pay any attention to it." Like most landlords, they just get a check from their tenants and make the necessary improvements to their property. End of story. But if the Attmans were paying more attention to what's happening on the Block, they'd know that its problems have little to do with the morality of sex among adults. The area is besieged by negative publicity over drug dealing, prostitution, employment of underage dancers, and the threatening atmosphere some civic and business leaders contend the Block creates in the middle of the downtown business district. If they were paying attention, the Attmans would know that last May four pipe bombs were found and defused in the Diamond Lounge, a few doors down from their Block property. They'd know that a club next door to their building, the Circus Bar, was ordered to sell its liquor license last October after a former doorman, convicted of dealing drugs from the club, told the Baltimore City Board of License Commissioners (aka the liquor board) that he thought it was "part of my duties" to sell cocaine from the bar. They'd know that in July 1998, the 408 Club was cited by the liquor board for employing two 16-year-old Baltimore County high-school students as dancers and using three rooms above the bar for prostitution. And they'd know that these incidents are just the tip of the iceberg. (For a fuller accounting of Block property owners and the records of businesses there, see "What's Around the Block".) But Joanne Attman doesn't want to hear about it. "That's ludicrous," she says of the idea that a Block employee considered drug dealing part of his job. "You can go anywhere and buy drugs anywhere in the city. You can buy them at school. They're being sold everywhere. So to focus in on the Block is absolutely ludicrous." She is adamant that the action on the Block is essentially harmless: "You know, most of the people down there are there to make a living and that's what they're doing—a clean living." With that, the interview ends abruptly. The way people make their living on the Block isn't causing ripples just in City Hall and law-enforcement circles; it is fast becoming a divisive issue within the red-light district's business community itself. Today, two separate entities—Baltimore Entertainment Center Inc. (BEC) and Downtown Entertainment Inc.—claim to represent the interests of Block businesses. Both groups, at least on the face of it, share the same goal: to clean up the Block's act so that its businesses can work with city leaders to promote the district as a destination for tourists and conventioneers. But their respective members don't see eye to eye on how to achieve that aim, according to Block sources. Today, Baltimore Entertainment Center is effectively defunct, although it is still recognized by many on the Block as an ongoing concern. BEC was formed in February 1997 and until a few months ago was represented by Baltimore attorney Claude Edward Hitchcock, a confidant of former Mayor Kurt Schmoke. At the time the group was launched, Hitchcock said it represented a "new breed of owner and operator on the Block" that is "trying to become better citizens and better neighbors." Hitchcock resigned as BEC's attorney in September; the following month, the group forfeited its right to operate in Maryland due to its failure to file property-tax returns—a rectifiable situation, should the taxes be brought up to date. (Attempts to speak with Frank Boston III, reportedly BEC's new attorney, were unsuccessful.) Days after Hitchcock left BEC, Downtown Entertainment was formed, with Hitchcock as its lawyer and Jacob "Jack" Gresser—the owner of the Gayety Building, a Block landmark, and another former BEC guiding force—as president. Gresser says Downtown Entertainment wants "to go in the direction of a partnership with the city, in respect of getting involved in the conventions that are coming to town, where the city will advertise these particular businesses in their convention brochures and throw the business our way, if possible." Ultimately, Gresser says, he wants the Block to become like Bourbon Street, New Orleans' famous playground of vice. So far, eight to 10 of the Block's two dozen adult-entertainment establishments have joined the new group, he says. Gresser says the splintering of BEC occurred over the course of last year, culminating about six months ago—"That's when we decided to go our different ways." While he's loath to speak for those who haven't joined Downtown Entertainment, he says there are "two distinct, different views of how people want to run their business down on the Block. Everybody runs their business differently. Everyone has a responsibility to run their business properly. I would just like to see everyone get together and go in one direction. We really don't need this diversification." That "diversification" has created to some bad blood. "This has not been a walk in the park," Hitchcock says. "I mean, I've gotten calls here in the office on my voice mail, you know, the use of the 'N' word, and 'Who the fuck do you think you are?' and all. One guy who was a part of [Downtown Entertainment] got his windows bashed in—both in his business and his car—and his family got threatening phone calls over the telephone at home. I've gotten it all. I mean, this has not been easy." Neither Gresser nor Hitchcock will go into detail about the causes of the split. Other sources familiar with the situation, who spoke on condition of anonymity, are less cagey—they claim the split is between clubs that host prostitution and clubs that don't. "Apparently the difference is private rooms, no private rooms," says one source. "If there are no private rooms, then you obviously can't have prostitution on the site." The clubs without private rooms are the ones moving into Downtown Entertainment, he says. Sources say the new group also wants police officers currently on the Block beat rotated out. "The policemen around there have been around there for years and have a bunch of friendships," one source says. "If you are there too long, familiarity can breed bad things." Hitchcock says Downtown Entertainment has "scheduled an appointment to talk with the new police commissioner [Ronald Daniel] to basically introduce this new organization to him, to give him a feel for what we intend to do, how we intend to run the businesses, [and] to affirm or reaffirm with him our willingness to be cooperative with the Baltimore City Police Department. In fact, we encourage the police department to be active—fair, but active—on the Block." Police spokesperson Robert Weinhold says Daniel "has had conversations with representatives from the Block" and recognizes that they want to make the red-light district as crime-free as possible. "We would expect the efforts of the Block representatives to continue, and that all of the establishments and the citizens who work there will be law-abiding in their business efforts." Eventually, Hitchcock says, Downtown Entertainment will seek a meeting with Mayor Martin O'Malley, but it has yet to broach the subject with him. For the time being, the new mayor's approach to managing the situation on the Block remains a mystery. Despite assurances that he would grant an interview for this article, repeated attempts to set up such a meeting were unsuccessful. O'Malley's press secretary, Tony White, eventually explained that the mayor has yet to formulate his opinions about the Block district and therefore would rather not discuss it at this time. "Being the entertainment mogul that he is, he's thinking about" the Block, White says, but this thinking "hasn't come to fruition yet." It would be a stretch to suggest that contributions to O'Malley's mayoral campaign last year will have a direct impact on his eventual stance. But several Block interests did pledge support for his candidacy, in all likelihood out of a desire to foster access to and good relations with their potent neighbor in City Hall. Between July and October of 1999, Block interests donated $6,400 to O'Malley's cause, according to campaign-finance reports. One of Gresser's businesses, Custom House News, gave $1,000, as did PP&G, which co-owns the strip club Norma Jean's and is headed by Pete Koroneos, secretary and treasurer of Downtown Entertainment. The law firm O'Malley worked for before he became mayor gave $2,000 to his campaign, and one of its partners, Joseph Omansky, has long represented Block interests. The remaining $2,400 came from other Block lawyers, owners, liquor licensees, and an accountant. The Block's generosity toward politicians is a long-established tradition—probably as old as the Block itself. The district sprang up almost immediately after the Great Baltimore Fire of 1904, with the Gayety Theater (opened in 1906 at its present site at 403 E. Baltimore St.) becoming its first landmark. Initially, penny arcades and vaudeville venues dominated, but after the repeal of Prohibition the area took off as a dense concentration of bars and burlesque houses. During the World War II years and into the 1950s, the Block's reputation spread nationally as striptease acts became the main attraction at many of the nightclubs and, as two out-of-town reporters wrote in 1951, "any and all forms of vice are tolerated and protected. There is a price for everything, and it's not much." With all of the fun and money being generated on the Block, heat from law enforcement was turned up. Various congressional inquiries and grand-jury investigations fingered the Block as an organized-crime stronghold in the 1950s and '60s, a place where the rackets, gambling and prostitution in particular, thrived and fueled corruption and violence. Even during its heyday—so romanticized by a legion of old-time Baltimoreans and local scribes—the Block was a dangerous place that spawned crime sprees and fear and trepidation among hand-wringing city residents. If the 1960s were bad on the Block from a criminal-justice standpoint, the '70s were much worse. Julius "The Lord" Salsbury, the acknowledged king of Block rackets, was finally convicted on federal charges in 1969, only to flee the country the following year. (Never brought to justice, he remains a legendary fugitive.) But with the end of Salsbury's reign—and perhaps because of the destabilizing effect of his absence—came an era of unprecedented violence in the district. When crime fighters did try to put the screws to the Block, they often ended up embarrassing themselves: A 1971 raid by federal agents produced little in the way of convictions and made law-enforcement appear groundlessly zealous in pursuit of justice for Block racketeers. With downtown's renewal into a modern entertainment district, however, the Block gained a sense of legitimacy, due largely to rose-colored memories of its former glory and its faded Damon Runyonesque character. Then-Mayor William Donald Schaefer spared the Block from his wide-swinging wrecking ball as he rebuilt downtown, and in 1977 it received a special designation as an entertainment district. But the Block's salad days were long gone; drugs and sleaziness continued to define its identity into the 1980s and '90s. As Schaefer moved from City Hall to the State House, his tolerance for the Block wore down. Late in his second term as governor, he ordered a four-month investigation of crime on the Block that culminated in a January 1994 Maryland State Police raid in which some 500 state troopers descended on the district and shut it down. Initially, the governor and his troopers made great claims—one drug kingpin and three distributors had been nabbed, an arsenal of guns had been confiscated, the back of criminal interests on the Block had been irreparably broken. But attempts to prosecute those arrested fell apart amid allegations of improprieties and faulty techniques among the investigators. Once again, law enforcement was left red-faced by its flawed attack on the tenderloin. Schaefer's raid occurred as his mayoral successor, Kurt Schmoke, was in the midst of his own attempt to put the Block out of his misery, by buying it out and relocating businesses. This economic attack failed, however—community leaders around the city feared porn shops and strip clubs would spring up in their backyards. Ultimately, after a flood of contributions to Schmoke's campaign committee from Block interests in late 1996, a détente was reached. Fronted by the Schmoke-friendly Hitchcock—who had previously represented other downtown business interests that hoped to end the Block once and for all—Block operators received a respite as City Hall promised to await improvements promised by the newly formed Baltimore Entertainment Center. The city held up its commitment, providing physical improvements such as new brick sidewalks in 1997, but so far the businesses haven't held up their end of the bargain by substantially cleaning up their acts. If and how O'Malley reacts remains to be seen. The mayor may still be forming his ideas on the future of the Block, but a new regulatory era is already underway. In November, the city liquor board started enforcing new rules that hold the threat of revocation of adult-entertainment licenses should club employees commit too many violations. Hitchcock says Downtown Entertainment welcomes the restrictions. "We frankly saw it as tightening of the regulations in a fashion that we all agreed needed to happen," he says. "We've had some very damaging rulings by the liquor board against some of those clubs down there. People are getting the message—you know, you do this stuff and you will lose your livelihood, period, end of story. You may be able to appeal it until it gets to some point of finality, but the liquor board's not playing about this because they have taken on a responsibility and their credibility is on the line." Perhaps even more significant than the new regulations, from a business standpoint, is a January 1999 court ruling that full nudity is legal at adult-entertainment establishments that opened before 1993. The ruling arose when the Spectrum Gentlemen's Club in East Baltimore appealed a nude-dancing violation and found a loophole in the law, which had been interpreted to require that dancers be partially clothed while performing. The decision was handed down by Circuit Court Judge Richard Rombro, in his last judicial act before retiring from the bench. (Unnoticed at the time was the fact that the judge's nephew, Stuart Rombro, is an attorney who represents Gresser's Custom House News.) Regardless, it's been good for business on the Block. Hitchcock downplays the ruling's practical significance. "There's no real difference," he says. "I mean, yeah, rather than you put a little star on the nipple, you can take the star off now." But he acknowledges that Baltimore strip clubs have become a "more marketable and a bigger revenue-generating business because you can basically say it's nude dancing." And a more marketable Block is a boon for Baltimore, says City Council member Nicholas D'Adamo, a Democrat whose 1st District includes the Block and many other adult-entertainment venues. "Let's be honest," asserts D'Adamo, who acknowledges that he patronizes Block establishments now and again. "Is it a plus for the city of Baltimore? I think it is. I think for out-of-towners to come to the city, it could be a stop on their agenda if they're staying downtown." He further maintains that Block businesses employ some 1,000 workers and should be recognized as job-providers. Of the allegations of vice associated with Block clubs, the council member says, "I think the press has blown it out of proportion. Sure, there are problems down there. But I think there are problems in every bar. It's just a matter of what you consider a problem. So why pick on the Block? "You show me a person a week's being killed on the Block, or a person a week's being stabbed and almost died—you show me numbers like that, we got a problem," D'Adamo continues. "But goddammit, there's a lot of streets in this city that have these problems that are a lot worse than the Block. We need to address that first." And, for the time being, it appears that's exactly what the city's going to do." (Van Smith, Baltimore City Paper, February 2-8, 2000)

|