|

|

|

|||||

|

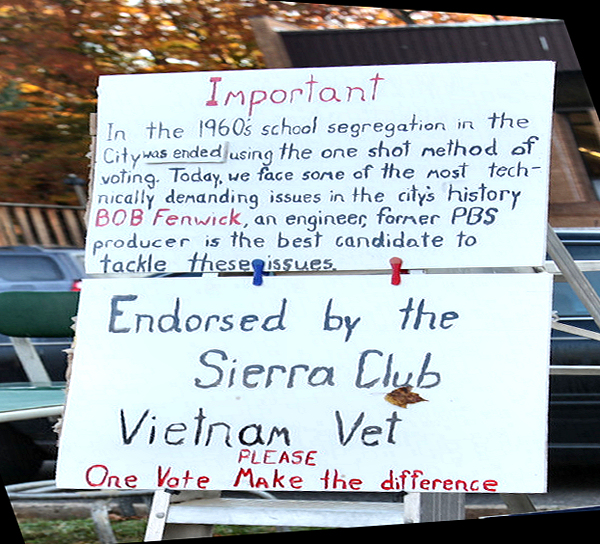

There were two open seats on the Charlottesville City Council in the recent election, so each voter in the City got two votes to use in selecting among the four candidates.  Single-shot voting represented a way to increase the chances for Independent candidate Bob Fenwick. His strong opposition to the Meadowcreek Parkway project gave him a basis of support among voters for whom that is their overwhelming issue. But for many of them, casting a second vote would have been a vote for one of the Democratic candidates, swelling those totals and making Fenwick's election less likely (in the end, he did not win a seat).  A sign posted near the Walker precinct on election day urged a single vote for Fenwick. To validate 'throwing away' the other vote, it made reference to the notion that single-shotting had, in the 1960s, lifted the City schools from the abyss of massive resistance. Not so, say Lloyd Snook and Paul Gaston. The integration of the City schools took place through court orders and the actions of the School Board (which was not then an elected body). Gaston comments, "This sign is nonsense, suggesting the author's unfortunate lack of knowledge of the past. Mr. Fenwick might read the 1962 report Tom Hammond and I wrote (copies are in Alderman library)." Snook's recollection (and family history--his father was President of the Venable School PTA at the time) is that no election was involved in ending school segregation in Charlottesville, and that only two people involved ran for office in the period immediately afterward. He says that Mitch Van Yahres was the first local leader to provide a voice of sanity, and was not elected to the City Council until after the final steps in desegregation had already been taken. And Tom Michie, who had been a member of the School Board during the conflict, was later elected to the House of Delegates in an election where only one vote could be cast for the slot. (Dave Sagarin, November 11, 2009)

|