|

|

|

|||||

|

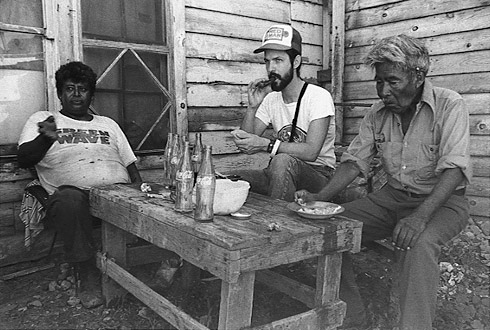

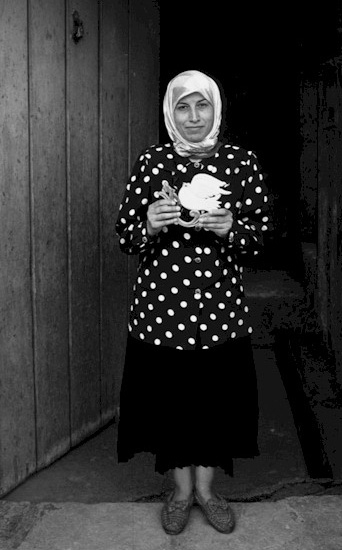

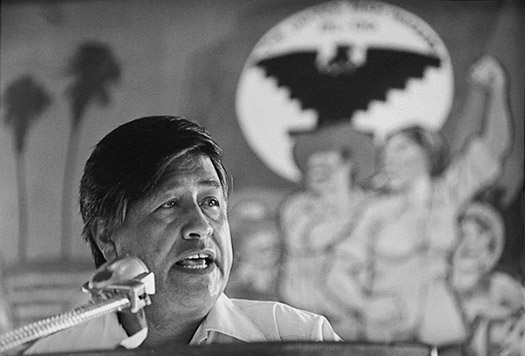

"Austin, our state of Texas, our country and our world are better places because Alan Pogue lives and works among us. His photos are passionate, eloquent pleas for a little more humanity, justice and democracy in our society. He's to photography what Thomas Paine was to pamphleteering." -Jim Hightower  Last fall I interviewed Austin photographer and social activist, Alan Pogue. I met him at a modest house in East Austin which headquarters the organization he founded - the Texas Center for Documentary Photography. Stuart Heady summarizes Alan's career well in the December 2001 issue of a Central Texas magazine called "The Good Life", ". . . For three decades he has traveled the globe taking photographs that documented the lives of the poor, the hungry, [and] the oppressed. His unflinching photographs, depicting prisoners on death row, Iraqis dying from the effects of a US embargo, or Palestinians corralled in the Occupied Territories of Israel, do not take advantage of his subjects but instead find and depict their humanity." Alan certainly gets around. Since I saw him last, he has traveled to Israel. But he was peripatetic even within the confined space of his office and studio. As I followed him and asked questions, he was finding this and organizing that. Yet throughout the interview process I was impressed by the essay like quality of his responses. He both takes photographs and puts them in context. He says ". . . It's a big challenge to get enough information in a series of pictures in order for the viewer to grasp what it all means. So in a lot of cases, the images are helpful but they are not enough. There has to be explanatory text for people who lack historical context." Bearing witness to the suffering and struggle of people in need, Alan has worked and traveled in Texas, the US, Latin America and the Middle East. He describes himself in the following way: I am a photographer. I have been a photographer for 33 years. But

the photography that I do all has to do with social justice. Almost all

of it has to do with people in need, in need of something - whether it is

farm workers or prisoners, people who are struggling for land or better

living conditions or having to do with some [other] unpleasant social reality.

(The following article is lengthy. If you choose to skim it, I hope that you will linger with the images interspersed with the text. Under each image except the last two is a link to a picture which, I believe, compliments the one shown. See what you think. If you would like to sample Alan's thought, I recommend the section entitled "A Man with a Key". Many topics which Alan cares about, including his role as a photographer, and the importance of history are treated there. In addition, that section gives you a good feel for how Alan thinks on his feet. The section entitled "Racism" which is immediately below is also very interesting. It has a couple of excellent stories.)  Racism I like to ask people who, like me, were raised in Texas and witnessed the end of legally sanctioned racial segregation, about their first experiences with racism. These people, like me, are white and their experiences vary according to the racial attitudes of their family and where they were raised in the lone star state. The most interesting stories come from people who lived in areas where the races actually brushed up against one another - where racial segregation had not fully achieved geographical separation. For children in this circumstance racism sometimes did not become apparent until an invisible line had been crossed - when a request for a playmate to come over for a sleep over or an invitation to a friend to come over for lunch was met with derision or something worse, or when they found out that the "aunt" who folded their clothes and washed their floors was not due true familial respect. I asked Alan about his childhood and how it affected his politics. He was raised in Corpus Christi - a city in South Texas, close to Padre Island. He went to a Cathedral School of the Catholic Church in the central business district of Corpus Christi. Most of his classmates were Latin American and there were a few Afro-Americans. It's not surprising that the subject of race came up. What is surprising is that his story had elements in common with the one told in Harper Lee's To Kill a Mockingbird: My father was a kind of a middle of the road Democrat. He was even

for Shivers [a conservative Texas Governor]. But he was not at all racist.

It's interesting he was from Smithville, Texas, which is not too far from

Austin. It's about 45 miles east. His father, my grandfather, drove a train

for the Katy & the Southern Pacific railroads. [So] my father grew up

in a very small town. Alan has photographed farm workers extensively. And it is significant that his sensitivity to racism against Hispanic Americans started at an early age. I asked him how his early experiences with racism prepared him for dealing with non-European cultures: I think it was very helpful. I remember one day I was in my father's

law office. I did my homework in the law library and his associates weren't

necessarily as enlightened as he was. And I remember I overheard these lawyers

talking about how they had moved into an expensive bedroom community so

that their children would not have to go to school with the Mexicans. So

I thought to myself, 'but these are the people I do go to school with. What's

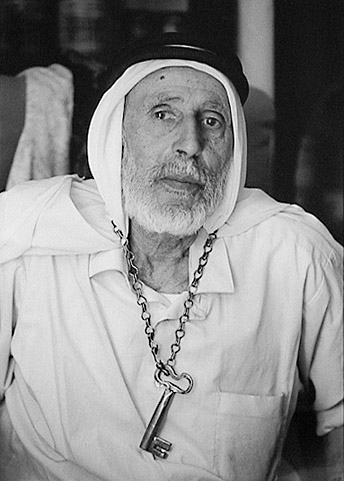

wrong with them? What's wrong with that?' A Man with a Key Obviously, Alan learned a lot about racism outside of the classroom. He had a similar experience finding out about politics. In high school he was a precocious and serious student with an interest in philosophy and sociology. But he acknowledges that his political education has been a product of life experiences and independent reading as well as formal education. In many ways this education began when he served in Vietnam, first with the Chaplaincy Corps and subsequently with the Medical Corps. It has continued, of course, through his university studies, his work and his travels For a number of years he has worked on peace and justice issues pertaining to Afghanistan, Israel, the Palestinians, Jordan and Iraq. However, he is emphatic that we avoid terms which refer too broadly to the various nations in that region and which ignore their historic and cultural differences: There isn't really, honest to goodness . . . such a thing as the Islamic World. There are lots of people who might be Moslem but there's [not] much to those terms. Afghanistan is so much different from Jordan. Iraq is so different from Saudi Arabia that it doesn't make any sense. Iraq, in particular, is a very secular country and women have a lot of freedom in the sense that they don't have to wear any particular kind of clothes and they can have any kind of job they want. This is vastly different from Saudi Arabia or Afghanistan. But then Jordan. . . Jordan has a good deal of freedom . . . so you have to go by a country to country basis. Life experiences can be our greatest teacher. But, at times, education on the road can be jarring. In an interview he had with Tom Parrish, Alan recounted the following exchange between him and Iraqi ceramic artist Neam Ahmed: I remarked to her [Neam Ahmed] that her work would sell well in the United States. And she shot back, 'It would sell well here if you stopped bombing us.'  Perhaps, because I am often surprised by my own naiveté concerning the world political scene and because I have impatience with the apparent intractable nature of many of its political problems, I asked Alan the following question: Craig: I was very struck by your photo of the Palestinian man with the key to the house that he was forced out of hung around his neck. To me the picture is very sad. My question is - Do you think that people is this country have poor attention for those types of images? Do we always seek a happy ending? Alan: Well, we do seek a happy ending. And, in order

to have that ending, people in general would have to know more history.

Americans are notoriously weak in historical knowledge. Newspapers tend

to tell you what happened yesterday. But they aren't going to give you a

cumulative number of events over the last 10 to 20 years. So, unless a person

goes far beyond what they can learn from the broadcast and print media (down

to papers, even magazines), if they don't read history books, they can't

possibly know what causes these problems. If they don't know what caused

the problem, they can't know what the solution might be. On the other hand,

if they do know the cause, then they can see the solution. So therein lies

the problem. It's education - not education in the sense of going to school

- but self-education. And, if they have that, then they can have the context

with which to understand these images.  Choices "Alan Pogue married his considerable artistry to the service of social justice early in his life and it's a marriage that has lasted to this day to the betterment of both his art and the causes it has served." - Gonzalo Barrientos, Texas State Senator It seems to me that Alan has made some extraordinary choices about the direction of his life. He is a talented person who has eschewed many of the material rewards he might have had if he had not dedicated himself to social justice work. I was curious about the challenges and rewards this entailed. Craig: I think that a lot of people imagine that the life of an artist and an activist is an ascetic existence. What is it really? Alan: Well, in my particular case, I guess it does have

some of these qualities, because, in order to do the work that I do, I have

to be willing to make a lot less money than I would if I were a commercial

photographer. If a person wants to do work that has to do with social change,

they have to realize there is no money in it. Because if you are selling

a product with what you do or if your photographic products are for sale,

then, because of that you'll be making money. The people that you are doing

the photography for intend to make money and then you'll get a percentage

of that money. The more money they're making, the more you'll make. While,

if you are working for social change, there's no money in that. No one's

making any money in that. And there is the fundamental difficulty.  Greed and Politics Despite the fact that Alan has been more active than most, he seems to have a lot of faith in the rest of us. In the interview I cited above, he said: "If enough truthful information is put before people, then they can make a decision. I believe they will make the right decision if they have the right information." But he warned: "If you make a bad political choice the result of that choice may not be instant. It may take a day, a week or a year for the result of your choice to have an effect that can be recognized. But the result of your choice will always be there, absolutely. So I definitely believe in truth at every level." I was curious why, if this was true, our nation makes such poor choices much of the time. This led him to a discussion of how greed influences politics: Craig: You seem to have faith that, if the people know the truth, they make the right decisions. How is it that those in power often make such inhumane decisions? Alan: Well, it's a problem of the system. Who can become

a politician and become successfully elected? - Only those with money or

a lot of access to money. So the kinds of people who can become elected

officials are circumscribed to people who are basically greedy. Greedy people

can do it. People who aren't motivated by greed operate at a tremendous

disadvantage in our political system. So certain personality types will

self-select and be selected because of the economics. You can't run for

state offices, especially state-wide office, if you don't have a million

dollars to begin with. If you were to run for governor you better have 20

million dollars to start with, at least.  Texas At the time I was visiting Alan, the political system there had definitely taken a different tack than the one he advocates. Several people I talked to felt that they had been disenfranchised by the recent redistricting of the state. The state legislature had successfully carved up the political map to the Republican Party's satisfaction. Longtime liberal congressman Lloyd Doggett's congressional district had been split into four parts given to 4 newly drawn districts, including one that stretched from Austin to the Mexican border. Molly Ivin's described the new map in the following way: . . . this map is a masterpiece, a veritable Dadaist work reminiscent of Salvador Dali's more lunatic productions. I asked Alan: Craig: Do you see anything hopeful about Texas politics? Alan: It's pretty bleak right now. Particularly in the way the Republicans are redistricting the state to cut out any competition. I always say that what the Iraqis would find out about democracy from Texas - what they would learn is that the Republican Party is pretty much like the Baath Party. You take over control and you cut out all the opposition so that there is no possible challenge to your political superiority. That's what the Baath Party did and that's what the Republican Party is doing now. So the lesson to be learned here now is that people who want political power [want] to further their own economic interest. They don't want democracy and, given the chance, they will do away with democracy so that they can have all the power they need to make as much money as they possibly can - that's the end they have in mind. I wanted to know how his work with farm workers had affected his perception of the state. Naturally, Alan answered with an eye toward history: Craig: You've done work with migrant workers and other disaffected groups. How has that effected you perception of the state as a whole? Alan: Austin may have been a very liberal place but Texas as a whole is still a very conservative state. The racism against Mexican Americans is profound and it's odd considering that the independence of the State of Texas was won with the help of Mexican Texans in the community. But, once independence was won, and independence was secured, their rights and privileges were lesser rather than greater. But particularly the farm workers - the farm workers were held in virtual serfdom and still are to a large degree in Texas and the rest of the country. I've seen a lot of them. I asked Alan about the hopes he had for his children: Alan: I have one son and D'Ann has here daughter so

that's always the question of what kind of world will your children grow

up in, and it's not a pretty picture on all fronts. Because politics and

economics effect the environment, because it effects all kinds of decisions

that impact the quality of the air we breathe and the water we drink and

just every part of our lives. I'm afraid that the same people who want ultimate

political power are blinded by their own greed and to the consequences of

what they are doing - so that fossil fuels are going to be used until there

are none left, all the trees are going to be cut down . . . Basically, we'll

have no oxygen. We are going to strangle ourselves. That's what's happening.

Further evidence of things on the move was elicited by a discussion of the Green Conference which had recently taken place in Austin. He also gave some advice to fellow activists: Alan: We just had the Green Conference here in Texas, which brought together people from all over the state and the country to talk about environmental issues. But people are sophisticated enough to know that the environment entails everything - every level of politics and economics. So you can't separate these things except as a matter of emphasis, and a person, an individual person, has to pick his/her target. A person can drive themselves crazy doing something about everything. So a person has to be aware of the full range of issues. But for their own mental and physical health they need to pick very specific issues to give their time to. And they have to make sure that they have time for themselves, for their family, their health, because I've seen a lot of burn out, seen a lot of people lose their mental and physical health by trying to do too many things. So you have to have a balance. Part of maintaining a sense of balance is, I think, realizing that we aren't in this alone. Those who fight for social justice have allies across space and across time. Alan's consistent references to the importance of history reminded me of a story about another Texan who had a keen regard for history's importance. I have a story I would like to tell about him. Years ago I attended a party held in honor of John Henry Faulk. Mr. Faulk was a noted humorist and storyteller from Texas whose radio career was short-circuited by McCarthyism in 1957. The party I attended was a farewell to Mr. Faulk and his wife, Elizabeth, who were moving from his hometown, Austin, to Madisonville, Texas. At the party, John Henry told the story of his fight against McCarthyism. He had been working for a CBS radio station in New York City when a group called AWARE blacklisted him. Despite eventual victory in a libel suit against this organization, it was years before CBS hired him again. He said that he used the period of enforced unemployment which followed his blacklisting to review the major histories and great historic documents of our country. He recalled fondly the support he received from family and friends. Mr. Faulk was a defender of the First Amendment and an enemy of bigotry. There is a common saying "Eternal vigilance is the price of liberty." (Wendell Phillips) The citizens of Austin have a durable reminder that you can be vigilant without being grim. Their central library is named for John Henry Faulk. I asked Alan about the Texans he admired. He mentioned Molly Ivins, Deceased Congressman Henry B. Gonzales, Congressman Lloyd Doggett, his state senator Gonzalo Barrientos, and his state representative Elliot Naishtat. Stacked on a stool in his office were pictures he had taken of Jim Hightower and Barbara Jordan. Despite his criticisms of the political process he asserts that you can't paint all politicians with the same brush. He praised, in particular, the rectitude of Henry B. Gonzales. Texas progressives usually have the deck stacked against them, but they know that they have to play the game anyway. Recently Molly Ivins said that liberals in Texas have learned: "If you wait to have a good time until you win, it might be an awfully long wait. So have fun now!" Alan enjoys his work.  Conclusion Alan Pogue is a person who made a decision to work for social justice in early adulthood. It is a decision which has affected many of his subsequent personal and professional choices. He is a serious, soft spoken guy who doesn't shy from making harsh judgments about how the world is being run. It's obvious that he has witnessed many painful realities. But he also keeps his eye out for the daily satisfactions and joys of the people he chooses to visit. Essentially, Alan is a teacher. Through his art and his intellect, he endeavors to see the world more clearly. He shares what he knows and how he came to know it. Finally, I would like to recount a conversation that I heard in the bullpen at work which impressed upon me the seriousness of the choices each of us makes. Frederico, or Fred as we call him, is, like me, a graying bus driver. He is also a Filipino emigrant, US citizen, and a member of the Army Reserves. Presently he is in California awaiting transport ultimately to Iraq. He is aware that he will be there during a particularly unstable period in which the US sponsored provisional government will attempt to begin functioning. I heard him say to another bus driver "I guess it's time to pay my debt." "What?" she inquired. "You took me in and now it's time to pay you back", he replied. She said "Well, I guess the same applies to me". The woman he was talking to was Afro-American. And, because of that, I heard something ironic in her response. But for her, I believe, her statement was simply an assertion of citizenship. She was acknowledging the debt we have to one another based on our shared history and our mutual love and respect. How we choose to discharge that debt is, of course, up to each of us to decide.  Alan is trying to bring to this country an Iraqi child, Isra Abdul Amir, who was hit by shrapnel from an American rocket. "The shrapnel severed her right arm below the shoulder, and she suffered chest and abdominal wounds. A metal fragment remains lodged in her skull." (Cole/Pogue) He and Cole Miller are trying to bring her to the United States. Go to the website they established for that purpose, http://www.nomorevictims.org/ , and find out how you can help. While you are at it, go to Alan's website, http://www.documentaryphotographs.com/, and see how you can get Alan to visit you, show his slides and tell you about their significance. I benefited from his company and I think you would too. Craig Anderson, March 27, 2004 [posted April 18, 2004]

|